A Crispy, Salty, American History of Fast Food

Adam Chandler’s new book explores the intersection between fast food and U.S. history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/eb/9ceb4ae3-6dc2-49a7-a93a-c718c25746a2/gettyimages-1025440958.jpg)

A food fight broke out on Twitter in the middle of February. It wasn’t over the sandwichiness of a hot dog or the right way to eat a slice of pizza, but instead was spurred on by a tweet from the Los Angeles Times’ Food section.

The paper had just released its “official fast food French fry rankings” and the food columnist, Lucas Kwan Peterson, dared to list In-N-Out, the beloved chain founded in the 1940s in Baldwin Park, east of L.A., at the absolute bottom.

One of Peterson’s colleagues registered her discontent tweeting sardonically, “hello i am the social media intern and have to share this but i totally dont [sic] agree with it.” In-N-Out fans, fuming that one longstanding Southern California institution would betray another, made their fury known across the social media platform and in the Times’ comments sections.

Preferences (and pride) may vary among regional chains—whether it’s In-N-Out in the West, Culver’s in the Midwest or Chick-Fil-A in the South—but U.S. consumers remain fast food fanatics. A Gallup survey showed 80 percent of Americans eat at fast food chains at least once a month.

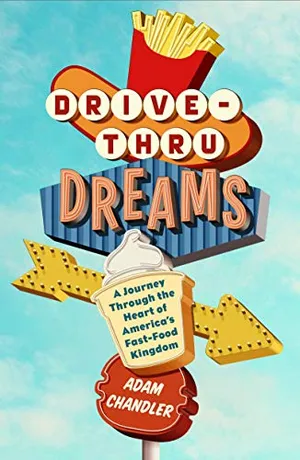

The passion Americans feel about fast food is at the heart of journalist Adam Chandler’s new book, Drive-Thru Dreams. “There are no inherited rites in America, but if one were to come close, it would involve mainlining sodium beneath the comforting fluorescence of an anonymous fast food dining room or beneath the dome light of a car,” he writes in the introduction. Chandler spoke with Smithsonian about the intersection between American history and fast food, its enduring popularity and how chains are changing to keep up with consumers.

Drive-Thru Dreams: A Journey Through the Heart of America's Fast-Food Kingdom

Drive-Thru Dreams by Adam Chandler tells an intimate and contemporary story of America―its humble beginning, its innovations and failures, its international charisma, and its regional identities―through its beloved roadside fare.

Why did you want to write this book?

I grew up in Texas where it’s not polarizing to eat fast food. It’s not divisive at all. Now I live in Brooklyn, New York, where it is. I think traveling between those two places a lot made me realize there’s a really interesting divide about this and made me want to explore it more.

What do you think makes fast food so quintessentially American? What does its history reveal about American history?

Fast food [took off] in large part because of the highway system that we built in the 1950s and the1960s. America started driving more than ever before and we rearranged our cities based on car travel, for better or worse. And it was a natural business response to the American on-the-go kind of lifestyle.

The founders of all these fast food chains are [part of] what we would call the quintessential American Dream. They were, by and large, from humble beginnings. They often grew up poor, didn’t achieve success until late in their life, and had all these setbacks. Colonel Sanders is a key example of somebody who struggled his entire life and then struck it rich with a chicken recipe he perfected while working at a gas station in southeastern Kentucky. There are all of these really impressive stories that I think, in another era, we would hold up as the ideal of American success.

And then there’s the food. The food is terrible, and it’s delicious, and it’s completely ridiculous and we love it. I mean, not everybody loves it, but it has this element of hucksterism to it, these insane ideas that get made. It’s a very American idea to just have the biggest, craziest burger or the wildest thing.

You can go into a McDonald’s, you can go into a Taco Bell, and you will see literally every demographic grouping there. Old, young, all races, all ages, all economic backgrounds kind of sharing a meal. There’re not a lot of places that offer that.

White Castle was the country’s first fast food chain when it opened in 1921 in Wichita, Kansas. What made it so appealing to Americans?

It fit the tech fascinations of the ’20s. There was a real assembly-line fervor that was raging across America. White Castle adopted this model—they had food that was prepared quickly in a very highly mechanized, highly systematized way. Every inch of the grill was dedicated for either the bread or the beef in small, square patties.

[White Castle] had these efficiencies built into it that really spoke to the fascinations of the era. And now it would sound weird, the idea that your experience there should be the same every single time and that every customer gets the exact same food over and over again. Something that’s very familiar is kind of seen as a negative now, but back then it absolutely was a cherished part of the experience.

For a long time, fast food was tied to suburban life, but in the late 1960s, companies made an effort to open franchises in urban areas. Can you talk about the dynamics at play there?

It’s a political third rail in a lot of ways because where fast food has ended up is, often times, a food desert in various communities. It is a place that people go to, along with corner stores, that don’t have a lot of nutritious and nutrient-dense foods. It definitely holds itself inadvertently as this sort of emblem of privation for certain communities.

Fast food moved into the urban centers late in the late 1960s and part of this was a result of the fact that they had saturated the suburbs and needed to expand. And this had a lot to do with the Civil Rights era, which is a fascinating sort of intersection in the story. Black-owned businesses, minority-owned businesses, were hoping to create economic bases in city centers where white flight and a lot of other social factors, like the building of the highways, had divided communities. Fast food was seen by activists and by the government—which would ultimately issue loans to help small businesses open fast food chains—as a solution to the problem.

The actual benefit or attraction of opening a fast food restaurant is self-evident. It’s familiar, it’s easily reproduced, and it’s popular and relatively cheap. Its profit margins are higher than a lot of other businesses, particularly grocery stores. So, this created kind of a perfect soup of all of these competing factors that united to spread fast food within urban centers and that’s where they took off.

How has the fast-food industry shaped other industries? And how did other industries shape it?

A lot of people credit, and critique, fast food with offering this kind of franchise model that you see all over the United States and all over the world, whether it’s haircuts or mattresses or gyms. Any kind of service [where] you see a franchise for a lot of people traces back to the roots of McDonald’s being a truly national brand.

What was interesting to me about fast food and its relationship with other businesses is, first of all, all kinds of weird, strange businesses feed into the fast food empire—whether it's creating packaging, or building equipment, or coming up with spices or flavors. Whenever McDonald’s creates a new product that requires a new piece of equipment to prepare it, they have to create an entire company to build that one product because that product is going to [be replicated] 30,000 times.

Fast food is more reactive, in a way, to the pushes and pulls of the American economy and that has to do with business trends. It has to do with how people are shopping and eating and consuming these days. So, as much as the drive-through has been and remains such a dominating force in the United States, we’re seeing Uber Eats, Seamless, DoorDash and all of these new companies involve themselves in fast food in a totally unexpected way. I personally can’t think of anything that sounds less appealing to me than having a burger you’re probably supposed to eat within 5 or 10 minutes delivered to your door in 20 or 30, but it’s proven to be extremely popular.

After the release of Morgan Spurlock’s documentary Supersize Me and the publication of Eric Schlosser’s book Fast Food Nation, there was a push in the 2000s for people to eat healthier and cut out fast food. How effective was that effort? Why didn’t we see a real change in fast food dining habits?

There have been efforts across the decades to push fast food to change. In the 1990s Kentucky Fried Chicken actually shortened its name to KFC, because “fried” was actually [considered] such a bad word.

In the book, I talk with [journalist] Michael Pollan about him having conversations with some of his acolytes and his followers, basically asking them, “How would you feel, if one day, you woke up and McDonald’s was all organic, no GMO, no high fructose corn syrup?” And the people responded [that they would be] disappointed. So, there’s an emotional component to it which is that we like fast food to be an indulgence, a treat, a kind of unhealthy, guilty pleasure.

A lot of people just don’t want the food to change. It’s not something that the core fast food consumer is really sweating in a way that you maybe hear about more on the coasts or in certain enclaves where the focus is more on changing dietary habits and improving the food systems.

Your book is full of entertaining anecdotes, like KFC Christmas in Japan. Do you have a favorite story from the book?

The creation of Doritos Locos Tacos is my favorite story in the book. Mostly because it involves a really terrific person who, in the most relatable way, was sitting on his couch eating Taco Bell and saw a Doritos commercial and thought, “This is exactly what I want to have—a Doritos-flavored taco shell.” He lobbied Frito-Lay to create the shells, and they said, “No, we can’t do that.”

So he started a Facebook group where he used his Photoshop skills to kind of put together these tableaus of famous pictures with Doritos Locos Taco shells in them. A lot of people started paying attention to it. And Taco Bell, which had actually created the idea 20 years before, and had shelved it because of corporate in-fighting, was planning to release the product and brought this guy along for the journey. It was a really, really fascinating, beautiful story. He lives to see the creation of the product, but dies very shortly thereafter. And his family and friends gather, and they all go out to Taco Bell after the funeral, and they eat their Doritos Locos Tacos.

Since you finished writing your book, Burger King introduced the plant-based Impossible Burger in many of its stores. Is this just the latest example of what industry insiders call “stealth health”? Do you think it’ll catch on?

Burger King was the first national chain to have a veggie burger on their menu and it’s had one since ’02 or ’03. What’s interesting about the Impossible Burger is that it fulfills criteria for people who want a more ecologically progressive burger as opposed to one that’s actually healthier for you. The Impossible Burger has GMOs, it’s highly processed, and it has about as many calories in many instances as a normal beef burger does especially once you build on the bread and the toppings and everything else. So, in a lot of ways, while it is impressive and while it does have its merits, from a health standpoint it’s more smoke-and-mirrors than anything. And so, if we’re talking about improving American diets, the Impossible Burger is probably not the answer.

I guess to add onto that there are some other interesting, incremental things that happened last year. Sonic, which is America's fourth-biggest burger chain, introduced burgers that they call the Blended Burgers and they have 70 or 75 percent meat and 25 percent mushroom, sort of a similar idea. And those have many fewer calories and actually taste pretty good. It’s a more incremental version of change to the burger process, it's “Try this out, it's a little healthier” and I think you can mentally make that adjustment a little bit easier than to something that is grown in a lab and has its own baggage. There’s a lot of tinkering going on and we're going to see what really sticks in the next coming years.

To write the book, you ate at fast-food chains all over the country. What’s your favorite one? Did that change from when you started?

Well, I have a nostalgic, historic connection to Whataburger, which is a Texas-born chain, because it was where I went as a kid and where my friends and I went in high school. I think I would be betraying my sweet Texas roots if I didn’t say it remains my favorite. I think they would ban me from going to the Alamo or something if I said it was something different.

[But] I always had a dangerous love affair with Taco Bell. That only increased during my time on the road because the way that people feel about Taco Bell is different than people feel about a lot of chains, at least national chains. Taco Bell is something special because everyone that loves Taco Bell, really loves Taco Bell. And everybody else thinks it’s the worst thing in the world. When I find a fellow Taco Bell traveler on the road, I immediately feel closer to that person.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.